Lymphoplasmacytic Lymphoma is a very rare cancer and can affect different parts of your body. No two people with LPL will have the same experience. For this reason, we do not know the typical signs and symptoms or best treatment options for LPL. The information on this webpage is based from case studies reported in medical literature. However, it is important for you to understand that your symptoms, tests and treatment may differ from what is on this page, based on your individual circumstances.

Speak with your haematologist or oncologist about what to expect in your individual circumstance.

Overview of Lymphoplasmacytic Lymphoma (LPL)

Lymphoplasmacytic Lymphoma (LPL) is an umbrella term for several different types of very rare cancers that begin in B-cell lymphocytes. The most common subtype of LPL is Waldenstroms Macroglobulinemia and this subtype is discussed separately on another page. You can find the link here.

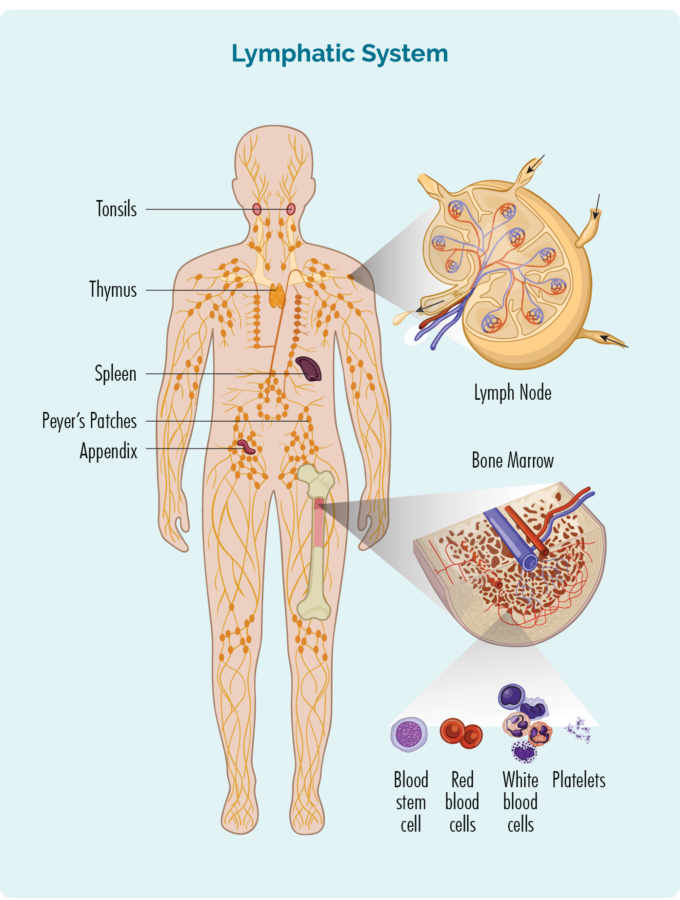

About B-cell Lymphocytes

B-cell lymphocytes are a type of white blood cell that support our immune system by fighting infection and disease. The most mature form of B-cell lymphocyte is called a plasma cell, and these cells make antibodies that stick to damaged or diseased cells and call other immune cells to the disease cells to repair or destroy it.

What happens in LPL?

LPL results in cancerous small B-cell lymphocytes, plasmacytoid lymphocytes and plasma cells invading your bone marrow. These different cells are all B-cell lymphocytes at different levels of development. The plasmacytoid lymphocyte is a cell changing from a small lymphocyte to a plasma cell.

Once in the bone marrow, these cells produce too much of either IgA, IgG or IgM antibodies. As a result of the extra cells and antibodies in the bone marrow, you may not be able to make enough of your health blood cells such as red cells, platelets and other white cells like neutrophils.

The cancerous cells and extra antibodies can also invade your lymph nodes, and organs within your lymphatic system such as your spleen, causing your lymph nodes and/or spleen to become enlarged. In some rarer cases LPL can invade “extra-nodal” areas of your body – meaning parts of your body other than your lymphatic system such as your:

- respiratory tract (lungs and airways)

- gut (stomach and bowels)

- bones

- kidney

- lining of your brain (meninges).

Non-Waldenstroms LPL subtypes

There are different subtypes of Non-Waldenstroms Lymphoplasmacytic Lymphoma, including:

- LPL with IgG proliferation

- LPL with IgA proliferation

- LPL with IgM proliferation without bone marrow involvement.

About Lymphoplasmacytic Lymphoma (LPL)

LPL is an indolent lymphoma, which means it is a very slow growing cancer, that may go through periods where it “sleeps” and other periods where it wakes up and actively produces too much antibody. It tends to be found more commonly in women than men, though men can develop it too. Most people diagnosed with LPL are around the ages of 65-69 years.

Not everyone with LPL will need to start treatment straight away because it is such a sleepy lymphoma. However, about 8 out of 10 people (80%) with LPL, will need to start treatment within about 6 months of being diagnosed.

Non-Waldenstrom’s LPL often have features that are similar to different subtypes of lymphoma or other blood cancers. This can make it very tricky to get an absolute diagnosis of any particular subtype.

Multidisciplinary meetings

With LPL being so rare, it is always a good idea to get opinions from other haematologists and members of the health care team for advice. You can ask your haematologist to present your case at a national lymphoma multidisciplinary meeting to get opinions from others before making a final decision on treatment.

Other blood cancers LPL can mimic

Some subtypes of lymphoma and other blood cancers that LPL can look and behave in the same way as LPL. As such, a diagnosis of LPL needs to consider all possibilities and can take some time. Some of the other subtypes of lymphoma that LPL can mimic include:

Antibodies

Antibodies are made by our Plasma Cells – the most mature form of B-cell Lymphocytes. They are important proteins that help our immune system recognise and fight germs, infections and diseased or damaged cells. Antibody proteins are called immunoglobulins which is often shortened to Ig.

Antibodies help our immune system to fight infection and disease by seeking out germs, diseased and damaged cells and sticking to them. Once stuck, the antibody sends out chemical messages to other immune cells to tell them to come and get rid of the cell. Some antibodies can also directly attack the diseased cells. However, they are very specific and each antibody will only recognise and stick to one receptor on one type of cell.

Click on the headings below to learn about the different antibodies.

Immunoglobulin Gamma

We have more IgG antibodies than any other antibody. They are shaped like the letter Y . However, if you have IgG LPL you have even more than usual and they may be too damaged to work properly to protect you from infection, because they were made by cancerous B-cells.

IgG is found mostly in our blood and other body fluids. These proteins have an immunological memory, so they remember the infections you had in the past and can identify them easily in the future.

Each time we have an illness we store some specialised memory IgG in our blood to protect us in the future.

If you do not have enough healthy IgG, you may get more infections or have difficulty getting rid of infections.

Immunoglobulin Alpha (IgA)

IgA is an antibody found mostly in our mucous membranes that line our gut and respiratory tract. Some IgA can also be in our saliva, tears and in breastmilk when mothers are breastfeeding.

IgM is the largest antibody we have and looks like 5 “Y”s together in the shape of a wagon wheel. It is the first antibody on site when we have an infection, so your level of IgM can increase during an infection, but then goes back to normal once the IgG or other antibodies are activated.

High levels of IgM is found in two different subtypes of lymphoplasmacytic lymphoma. The most common of all LPLs is Waldenstroms Macroglobulinemia where the extra IgM is found in your blood and bone marrow. This is discussed on another page here. In Non-Waldenstoms IgM LPL the the IgM antibody is not found in your bone marrow.

Problems with IgM can lead to you getting more infections than usual. When you have too much IgM your blood can become too thick because the IgM antibodies are quite big. Hyperviscous is a term used to describe your blood when it becomes too thick. Symptoms of hyperviscosity can include:

- headaches

- changes to your eyesight or hearing

- fatigue – extreme tiredness and weakness not improved with rest or sleep

- high blood pressure or changes to your heart rhythm

- muscle cramps

- confusion

- seizures

- low blood counts.

Immunoglobulin Epsilon (IgE)

Immunoglobulin Delta (IgD)

IgD is one of the least understood antibodies. However, what is known is that it is produced by plasma cells, and is usually found attached to other mature B-cell lymphocytes in our spleen, lymph nodes, tonsils and the lining of our mouth and airways (mucous membranes).

A small amount of IgD can also be found in our blood, lungs and airways, tear ducts, middle ear. IgD is thought to encourage mature B-cell lymphocytes to become plasma cells. It is thought to be important at preventing respiratory infections.

IgD is often found together with IgM, however it is not clear on how or if they work together.

Kappa, Lambda, Heavy and Light Chains

There are other terms you might hear your doctor talk about when talking about your antibodies. These include kappa or lambda and heavy and light chains.

There are other terms you might hear your doctor talk about when talking about your antibodies. These include kappa or lambda and heavy and light chains.

If you look at the picture of antibody here, you will see it looks like the letter Y with extra bits, one on either side at the top. The blue area is referred to as the heavy chain and the purple area is referred to as the light chain. The heavy and light chains are separate proteins that link up to make the immunoglobulin.

Heavy chains can be either A, D, E, G or M (which makes it an IgA, IgD, IgE, IgG or IgM) and light chains can be kappa or lambda. The antibody has two heavy chains and two light chains. The two heavy chains are always the same and the two light chains are always the same. For example, you:

- can have an IgG antibody with kappa light chains or IgG antibody with lambda light chains

- cannot have an IgG antibody with kappa and lambda light chains.

Both kappa and lambda can be found on any type of immunoglobulin (antibody). In some cases, your body might make too many light chains for the number of heavy chains, so you will have extra light chains in your blood and bone marrow – These are called “free” light chains.

Symptoms of Lymphoplasmacytic Lymphoma (LPL)

Due to the slow growing nature of LPL, you may not have symptoms when you are diagnosed. However, many people will experience symptoms at some point.

Common symptoms you may get with LPL include:

- Swollen lymph nodes

- An enlarged spleen that can cause a feeling of fullness in your tummy even if you haven’t eaten much, pain or discomfort in the left side of your abdomen or chest, fatigue and dizziness.

- Changes to blood counts including low red cells (anemia) or platelets (thrombocytopenia), high lymphocytes and high lactate dehydrogenase (LDH).

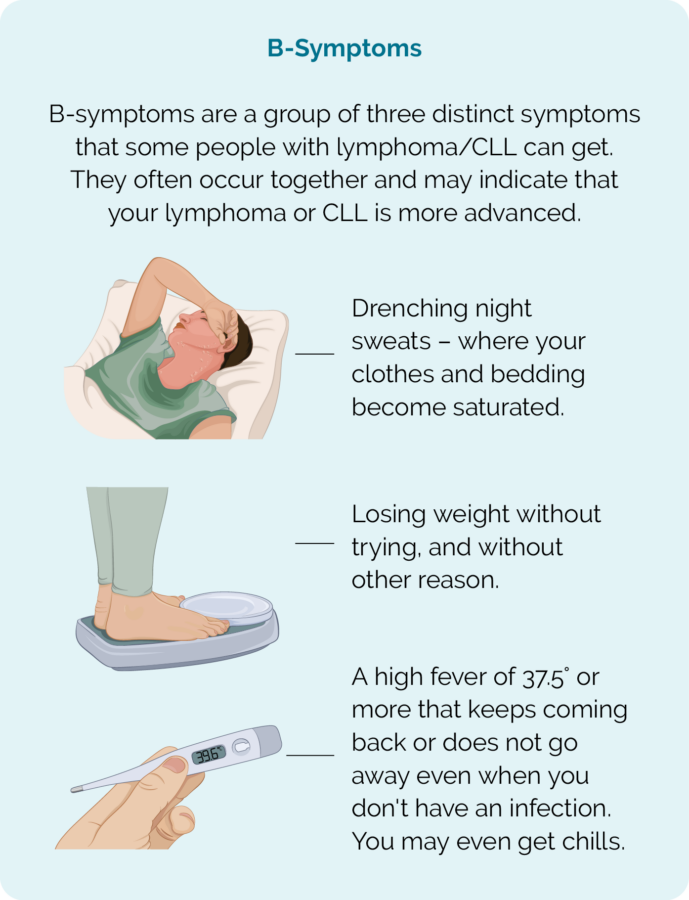

- B-symptoms (see picture below).

Other symptoms of LPL

While the above symptoms may affect anyone with LPL, some symptoms may be related to the part of your body the LPL is growing. As an example, if the LPL is growing in your stomach or bowels you may have:

- indigestion or heartburn

- changes to your appetite

- weight loss

- vomiting

- bloating

- bleeding when you go to the toilet

- B-symptoms.

Diagnosis and Staging of LPL

You may be diagnosed with WM after you have a blood test. But your doctor will want to do some more tests to confirm this and look at what parts of your body are affected. Some of these tests will include:

- More blood tests

- Urine (wee) tests

- Bone marrow biopsy

- Computed tomography (CT) scan

- PET scan

- Tests on your heart, liver and kidneys

Your treating heamatologist or oncologist will work out the best tests for you based on:

- your symptoms and how the LPL is affecting your organs

- the location of your LPL

- your blood results

- IgG, IgA or IgM antibody levels.

You may have one or more tests from the above list, or something altogether different depending on your individual circumstance.

Treatment

You may not need to have any treatment for your LPL, if you are not getting symptoms and the LPL is not actively growing. But if you do not need actively treatment, you will still me monitored by your haematologist. During this time of monitoring you will continue to have blood tests and physical examinations. This monitoring period is called Watch & Wait (or active monitoring). This way if there are any changes to how your LPL is behaivng or affecting you, the haematologist can pick it up early and recommend treatment.

You may need to start treatment if your:

- symptoms are troubling you

- antibody levels are too high

- heamoglobin or platelets (blood cells) are too low

- lactate dehydrogenase (LDH blood test) is too high

- other concerns as per your haematologist.

Before you start treatment

Before you start treatment, let your doctor know if you are hoping to have children in the future. Many anti-cancer treatments can affect your fertility, or cause harm to unborn babies, so it is important to talk to your doctor about these things. In some cases, they may be able to organise some extra treatments to increase your chances of getting pregnant, or getting someone else pregnant in the future.

There are also other things you should talk to your doctor about, but it can be hard to know what questions to ask when you are first diagnosed. To help guide your conversation we have put together some questions you may like to ask. Click on the link below to download our Questions to ask your doctor.

Treatment options

The treatment options you are offered will depend on your:

- location of your LPL

- symptoms and how the LPL is affecting your body

- age and overall health

- overall health and any other illnesses you may have or medications you are taking

- personal preferences after you have all the information you need.

However, some treatment options may include any of the following.

Chemotherapy is a name used to describe medications that destroy fast-growing cells and are often effective at treating cancer. These medications can’t tell the difference between hast-growing healthy cells or fat-growing cancerous cells, so your healthy cells can also be affected. This can result is some common symptoms such as:

If you are getting lots of symptoms, or your LPL is actively growing you may be offered treatment with chemotherapy.

Monoclonal antibodies are a type of medication that uses antibodies to identify cancer cells. The antibodies seek out and stick to certain proteins on the surface of the lymphoma cell. They can then start attacking the lymphoma cell, but also send out signals to bring more immune cells to the lymphoma to fight it.

Targeted therapies can be different types of treatment. They may include some monoclonal antibodies that target specific proteins on the lymphoma cell, or they might be other medications taken as tablet.

Some of these can block different proteins on, or inside the lymphoma cell that the lymphoma needs to keep growing. By blocking the proteins, the lymphoma can no longer grow, and eventually dies.

Plasmapheresis is a procedure that swaps out diseased parts of your blood plasma (and the cells and protiens in it) and replaces it with plasma from healthy donors.

Plasma is the liquidy part of your blood, and when your red blood cells are removed from it, it is a yellowy straw colour. Your plasma is filled with many proteins including the IgG protein and plasma cells (remember these are the most mature B-cells that make antibodies).

During plasmapheresis you will be connected to a machine called an apheresis machine. Your blood will slowly be drawn out and processed in the machine and the plasma will be removed. The new donated plasma will then be mixed with the rest of your blood and returned to you. this procedure can take several hours as only a small amount of blood can be removed at a time.

Blood transfusions may be offered to you if your healthy blood cells become too low. This can happen when the cancerous lymphoma cells and extra antibodies start to crowd your bone marrow so there is no room for your marrow to make new healthy cells.

Blood transfusions are not a treatment for your LPL but are supportive treatment to lessen your symptoms and prevent complications from low blood cells.

Transfusions may include red blood cells or platelets.

Some people have infusions of IVIG. This is an infusion of IgG that has been donated by blood donors. This is not uncommon for people who have had cancer of B-cell lymphocytes – as it is the mature from of B-cells (called plasma cells) that make the antibodies. Many treatments, including rituximab and obinutuzumab also are designed to attach to a protein on the B-cell so that it can be destroyed. Unfortunately, the protein targeted by these medications is found on cancerous B-cells as well as healthy B-cells. Some people who have had these treatments may also need an infusion if IVIG.

Follow-up care

Once treatment has completed, post treatment staging scans are done to review how well the treatment has worked. The scans will show the doctor if there has been a:

- Complete response (CR or no signs of lymphoma remain) or a

- Partial response (PR or there is still lymphoma present, but it has reduced in size)

If all goes well regular follow-up appointments will be made for every 3-6 months to monitor the below:

- Review the effectiveness of the treatment

- Monitor any ongoing side effects from the treatment

- Monitor for any late effects from treatment over time

- Monitor signs of the lymphoma relapsing

These appointments are also important so that the patient can raise any concerns that they may need to discuss with the medical team. A physical examination and blood tests are also standard tests for these appointments. Apart from immediately after treatment to review how the treatment has worked, scans are not usually done unless there is a reason for them. For some patient’s appointments may become less frequent over time.

Prognosis for Lymphoplasmacytic Lymphoma (LPL)

Due to being so rare, the overall prognosis for LPL is not known, though it is thought to be similar to those with LPL subtype Waldenstroms Macroglobulinemia.

Like most indolent subtypes of lymphoma, LPL cannot be cured. Instead, if you need treatment the aim will not be to cure but to manage the disease. This means keeping your antibody levels at a level that does not cause damage to your organs or cause you to get uncomfortable symptoms.

Most people get a really good response from treatment, and go into remission, however because we cannot cure LPL, it is common for it to come back (relapse) and for you to need more treatment at a later time. For some people, it may be months, and for others it could be years before you need more treatment.

Relapsed or refractory LPL

Some people with lymphoma who get a good response from treatment may relapse, which is when the lymphoma comes back after a time of remission. In rare cases your lymphoma may not respond to the first-line treatment (refractory). If you have relapsed or have a refractory LPL, you may need to start treatment again, or start a new treatment. This next lot of treatment will be called second-line treatment.

Before you start the next treatment, your doctor will consider several things while trying to find the best treatment for you including:

- how long it has been since your last treatment and how well it worked for you

- how long you have been in remission for

- side-effects you had with previous treatments

- your age and general well-being

- your preferences once you have all the right information to make the best choice for you.

Depending on your individual circumstance. You may be offered the same treatment you had before if it worked well, and you have been in remission for several years. You may also be offered one of the other treatments listed above. If you need to start second-line treatment, it is a good idea to ask your doctor about any clinical trials you may be eligible for.

Clinical Trials – Treatments under investigation

There are new clinical trials starting all the time and it is a good idea to keep up to date with what new treatments are being tested to improve the treatment, or quality of life for people with WM. If you are interested in participating in a clinical trial, you can ask your doctor if you meet the inclusion criteria for the study.

ClinTrial Refer is a good website that lists the different clinical trials available. You can access it by clicking here, and type in the search bar what condition you have that you would like to find a clinical trial for such as “B-cell lymphoma”.

Health and wellbeing

A healthy lifestyle, or some positive lifestyle changes after treatment can be a great help after you finish treatment. Making small changes such as eating well and increasing your overall fitness can improve your health and wellbeing and help your body to recover. There are many self-care strategies that can help during your recovery. Click on the link for more tips on living well.

Summary

- Lymphoplasmacytic Lymphoma (LPL) is a very rare subtype of Non-Hodgkin Lymphoma and has different subtypes.

- Non-Waldenstroms LPL is so rare that little is known about it. As such, there are no “gold standard” treatments options.

- Your haematologist will consider your symptoms and the individual changes involved in your LPL to decide the best treatment for you.

- LPL can look similar to other subtypes of lymphoma and you may need extra tests to get a definite diagnosis.

- Some people with LPL do not treatment straight away and will go onto Watch & Wait, but most people with Non-Waldenstroms LPL will need treatment within 6 months of being diagnosed.

- You can ask your haematologist to present your case at a national lymphoma multidisciplinary meeting to hear other haematologists and health professionals opinions on the best way to manage your LPL.

- You are not alone, you can contact one of our Lymphoma Care Nurses by clicking on the Contact Us button on the bottom of the screen.