Overview of Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia (CLL) / Small Lymphocytic Lymphoma (SLL)

CLL is more common than SLL and is the second most common indolent B-cell cancer in people over 70 years of age. It is also more common in men than in women, and very rarely affects people less than 40 years of age.

Most indolent lymphomas are not curable, which means once you have been diagnosed with CLL / SLL, you will have it for the rest of your life. However, because it is slow growing, some people can live a full life without symptoms and never need any treatment. Many others though, will get symptoms at some stage and need treatment. The goal of treatment is usually to either put the lymphoma into remission, or to improve any symptoms you may have.

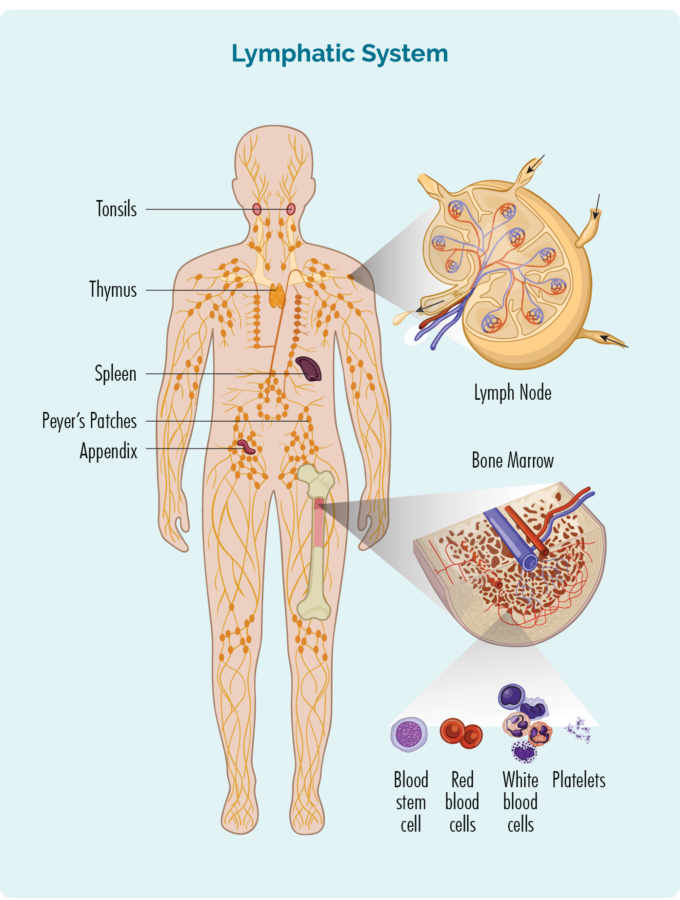

To understand CLL / SLL, you need to know a bit about your B-Cell lymphocytes

B-Cell lymphocytes:

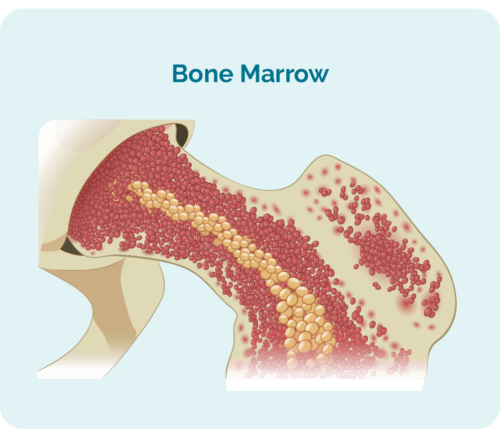

- are made in your bone marrow (the spongy part in the middle of your bones), but usually live in your spleen and your lymph nodes.

- are a type of white blood cell.

- fight infection and diseases to keep you healthy.

- remember infections you had in the past, so if you get the same infection again, your body’s immune system can fight it more effectively and quickly.

- can travel through your lymphatic system, to any part of your body to fight infection or disease.

What happens to your B-cells when you have CLL / SLL?

When you have CLL / SLL your B-cell lymphocytes:

- become abnormal and grow uncontrollably, resulting in too many B-cell lymphocytes.

- do not die when they should to make way for new healthy cells.

- grow too quickly, so they often don’t develop properly and cannot work properly to fight infection and disease.

- can take up so much room in your bone marrow that your other blood cells, such as red blood cells and platelets may not be able to grow properly.

Understanding CLL/ SLL

Professor Con Tam, a Melbourne based CLL/ SLL expert haematologist explains CLL/SLL and answers some of the questions you may have.

This video was filmed in September 2022

Patient experience with CLL

No matter how much information you get from your doctors and nurses, it can still help to hear from someone who has experienced CLL / SLL personally.

Below we have a video of Warren’s story where he and his wife Kate share their experience with CLL. Click on the video if you would like to watch.

Symptoms of CLL / SLL

CLL / SLL are slow growing cancers, so you may not have any symptoms at the time you are diagnosed. Often, you will be diagnosed after having a blood test, or a physical exam for something else. In fact, many people with CLL / SLL live long healthy lives.

However, you may develop symptoms at some point while living with CLL / SLL.

Symptoms you might get

- fatigued which is unusual, extreme tiredness and weakness. This type of tiredness does not get better after a rest or sleep

- feeling out of breath

- bruising or bleeding more easily than usual

- infections that don’t go away, or keep coming back

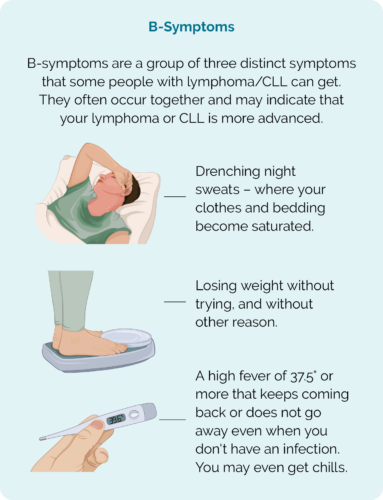

- sweating at night more than usual

- losing weight without trying

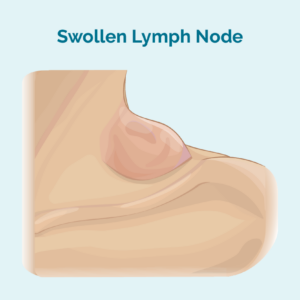

- a new lump in your neck, under your arms, your groin, or other areas of your body – these are often painless

- Low blood counts such as:

- Anaemia – low haemoglobin (Hb). Hb is a protein on your red blood cells that carries oxygen around your body.

- Thrombocytopenia – low platelets. Platelets help your blood to clot so you don’t bleed and bruise to easily. Platelets are also called thrombocytes, which is where the name thrombocytopenia comes from.

- Neutropenia – Low white blood cells called neutrophils. Neutrophils fight infection and disease.

- B-Symptoms (see picture)

When to seek medical advice

There are often other reasons for these symptoms, such as infection, activity levels, stress, certain medication or allergies.

But it is important that you see your doctor if you experience any of the above symptoms that last for more than a week, or if they come on suddenly without a known cause.

How is CLL / SLL diagnosed

It can be difficult for your doctor to diagnose CLL / SLL. Symptoms are often vague, and similar to those that you may have with other more common illnesses, such as infections and allergies.

You also may not have any symptoms, so it is difficult to know when to look for CLL / SLL. But if you do go to your doctor with any of the symptoms above, they may want to do a blood test and physical examination.

In other cases, you may have a blood test or scan for something else, and when the results come back, your doctor may suspect you have CLL/SLL or some other condition that needs more tests.

If they suspect you may have a blood cancer like lymphoma or leukemia, they will recommend more tests or refer you to a haematologist or oncologist to get a better picture of what is going on.

- A haematologist is a doctor with extra training and expertise in looking after people with conditions affecting their blood, including blood cancers.

- An oncologist is a doctor with extra training and expertise in looking after people with cancer.

Types of Biopsies

To diagnose CLL / SLL you will need biopsies of your swollen lymph nodes, and your bone marrow. A biopsy is when a small piece of tissue is removed and examined in the laboratory under a microscope. The pathologist will then look at the way, and how fast your cells are growing.

There are different ways to get the best biopsy. Your doctor will be able to discuss the best type for your situation. Some of the more common biopsies include:

Excisional node biopsy

This type of biopsy removes a whole lymph node. If you have a swollen lymph node close to your skin that is easily felt, you will likely have a local anaesthetic to numb the area. Then, your doctor will make a cut (also called an incision) in your skin near, or above the lymph node. Your lymph node will be removed through the incision. You may have stitches after this procedure and a little dressing over the top.

If the lymph node is too deep for the doctor to feel, you may need to have the excisional biopsy done in a hospital operating theatre. You may be given a general anaesthetic – which is a medicine to put you to sleep while the lymph node is removed. After the biopsy, you will have a small wound, and may have stitches with a little dressing over the top.

Your doctor or nurse will tell you how to care for the wound, and when they want to see you again to remove the stitches.

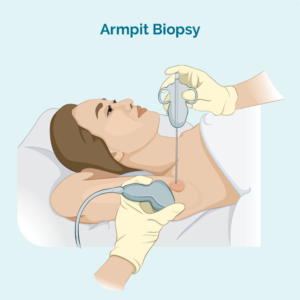

Core or fine needle biopsy

This type of biopsy only takes a sample from the affected lymph node – it does not remove the whole lymph node. Your doctor will use a needle or other special device to take the sample. You will usually have a local anaesthetic.

If the lymph node is too deep for your doctor to see and feel, you may have the biopsy done in the radiology department. This is useful for deeper biopsies because the radiologist can use an ultrasound or X-ray to see the lymph node and make sure they get the needle in the right spot.

A core needle biopsy provides a larger biopsy sample than a fine needle biopsy.

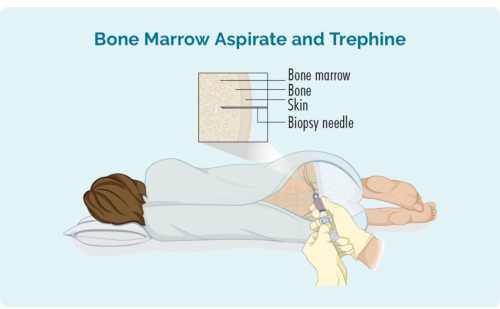

Bone Marrow biopsy

This biopsy takes a sample from your bone marrow in the middle of your bone. It is usually taken from the hip, but depending on your individual circumstances, may also be taken from other bones such as your breast bone (sternum).

You will be given a local anaesthetic and may have some sedation, but you will be awake for the procedure. You may also be given some pain relief medication. The doctor will place a needle through your skin and into your bone to remove the small bone marrow sample.

You may be given a gown to change into or be able to wear your own clothes. If you wear your own clothes, make sure they are loose and provide easy access to your hip.

Testing your biopsies

Your biopsy and blood tests will be sent to the pathology and looked at under a microscope. This way the doctors can find out if the CLL / SLL is in your bone marrow, blood and lymph nodes, or if it is limited to only one or two of these areas.

The pathologist will do another test on your lymphocytes called “flow cytometry”. This is a special test to look at any proteins or “cell surface markers” on your lymphocytes that help to diagnose CLL / SLL, or other subtypes of lymphoma. These proteins and markers can also give the doctor information about what type of treatment may work best for you.

Waiting for results

It can take up to several weeks to get all your test results back. Waiting for these results can be a very difficult time. It may help to talk to family or friends, a councillor or contact us at Lymphoma Australia. You can contact our Lymphoma Care Nurses by emailing nurse@lymphoma.org.au or calling 1800 953 081.

You may also like to join one of our social media groups to chat to others who have been in a similar situation. You can find us on:

Staging of CLL / SLL

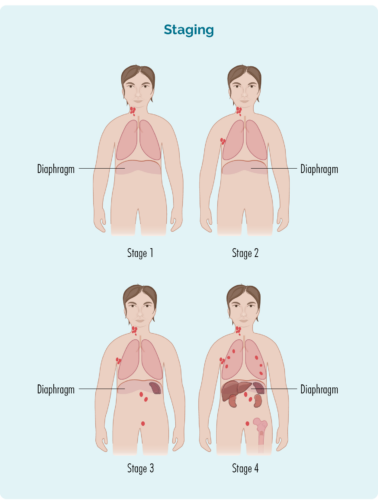

Staging is the way your doctor can explain how much of your body is affected by the lymphoma, and how the lymphoma cells are growing.

You may need to have some additional tests to find out your stage.

To find out more about staging, please click on the toggles below.

Additional tests you may have to see how far your CLL / SLL has spread include:

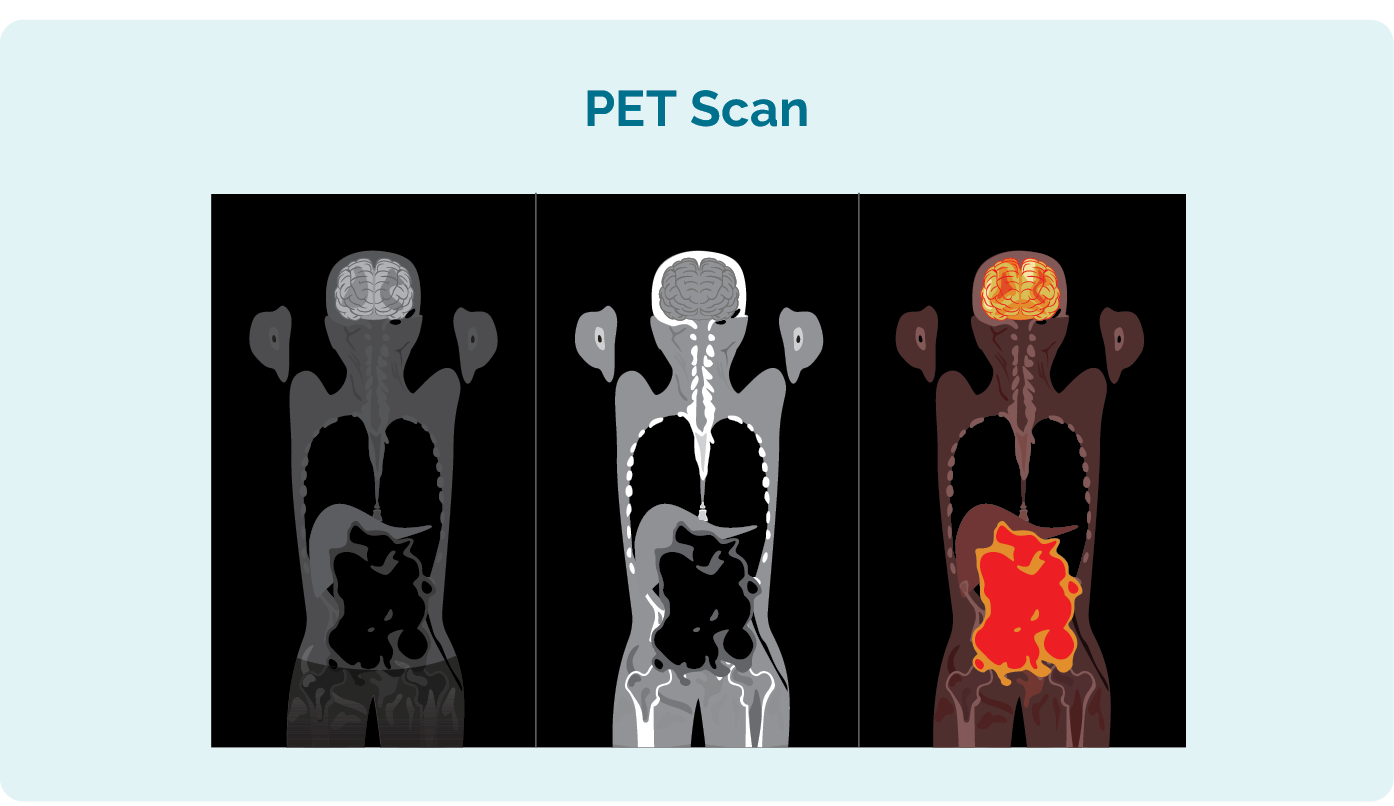

- Positron emission tomography (PET) scan. This is a scan of your whole body that lights up areas that may be affected by the CLL / SLL. The results may look similar to the picture to the left.

- Computed tomography (CT) scan. This provides a more detailed scan than an X-ray, but of a particular area such as your chest or abdomen.

- Lumbar puncture – Your doctor will use a needle to take a sample of fluid from near your spine. This is done to check if your lymphoma is in your brain or spinal cord. You may not need this test, but your doctor will let you know if you do.

One of the main differences in CLL / SLL (apart from their location) is in the way they are staged.

What does staging mean?

After you have been diagnosed, your doctor will look at all your test results to find out what stage your CLL / SLL is at. Staging tells the doctor:

- how much CLL / SLL is in your body

- how many areas of your body have the cancerous B-cells and

- how your body is coping with the disease.

This staging system will look at your CLL to see if you do, or do not have any of the following:

- high levels of lymphocytes in your blood or bone marrow – this is called lymphocytosis (lim-foe-cy-toe-sis)

- swollen lymph nodes – lymphadenopathy (limf-a-den-op-ah-thee)

- an enlarged spleen – splenomegaly (splen-oh-meg-ah-lee)

- low levels of red blood cells in your blood – anaemia (a-nee-mee-yah)

- low levels of platelets in your blood – thrombocytopenia (throm-bow-cy-toe-pee-nee-yah)

- enlarged liver – hepatomegaly (hep-at-o-meg-a-lee)

What each stage means

| RAI stage 0 | Lymphocytosis and no enlargement of the lymph nodes, spleen, or liver, and with near normal red blood cell and platelet counts. |

| RAI stage 1 | Lymphocytosis plus enlarged lymph nodes. The spleen and liver are not enlarged and the red blood cell and platelet counts are normal or only slightly low. |

| RAI stage 2 | Lymphocytosis plus an enlarged spleen (and possibly an enlarged liver), with or without enlarged lymph nodes. The red blood cell and platelet counts are normal or only slightly low |

| RAI stage 3 | Lymphocytosis plus anaemia (too few red blood cells), with or without enlarged lymph nodes, spleen, or liver. Platelet counts are near normal. |

| RAI stage 4 | Lymphocytosis plus thrombocytopenia (too few platelets), with or without anaemia, enlarged lymph nodes, spleen, or liver. |

*Lymphocytosis means too many lymphocytes in your blood or bone marrow

Your stage is worked out based on :

- the number and location of lymph nodes affected

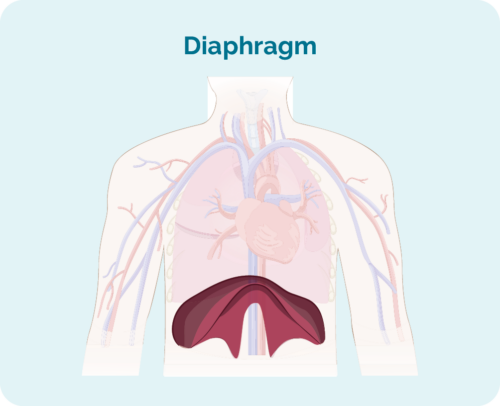

- if the affected lymph nodes are above, below or on both sides of the diaphragm (Your diaphragm is a large, dome-shaped muscle under your rib cage that separates your chest from your abdomen)

- if the disease has spread to the bone marrow or to other organs such as the liver, lungs, bone or skin

| stage 1 | one lymph node area is affected, either above or below the diaphragm* |

| stage 2 | two or more lymph node areas are affected on the same side of the diaphragm* |

| stage 3 | at least one lymph node area above and at least one lymph node area below the diaphragm* are affected |

| stage 4 | lymphoma is in multiple lymph nodes and has spread to other parts of the body (e.g., bones, lungs, liver) |

Additionally, there may be a letter “E” after you stage. The E means that you have some SLL in an organ outside of your lymphatic system, such as your liver, lung, bones or skin | |

Questions for your doctor before you start treatment

Doctors’ appointments can be stressful and learning about your disease and potential treatments can be like learning a new language. When learning

It can be difficult to know what questions to ask when you are starting treatment. If you don’t know, what you don’t, how can you know what to ask?

Having the right information can help you feel more confident and know what to expect. It can also help you plan ahead for what you may need.

We put together a list of questions you may find helpful. Of course, everyone’s situation is unique, so these questions do not cover everything, but they do give a good start.

Click on the link below to download a printable PDF of questions for your doctor.

Understanding your CLL / SLL genetics

There are many genetic factors that may be involved in your CLL / SLL. Some may have contributed to the development of your disease, and others provide useful information about what the best type of treatment is for you.

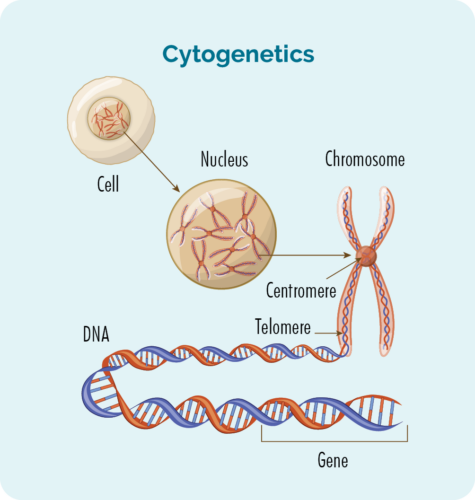

To find out what genetic factors are involved you will need to have cytogenetic tests done.

Cytogenetic Tests

Cytogenetics tests are done by a pathologist on your blood and biopsies. The pathologist looks for changes in your chromosomes or genes.

You may not need to have the cytogenetic tests done when you are first diagnosed. However, it is very important to have these tests BEFORE you start any treatment.

Chromosomes

We usually have 23 pairs of chromosomes, but if you have CLL / SLL your chromosomes may look a little different.

All of the cells of our body (except for red blood cells) have a nucleus which is where our chromosomes are found. Chromosomes inside cells are long strands of DNA (deoxyribonucleic acid). DNA is the main part of the chromosome that holds the cell’s instructions. Our DNA is made up of many different genes.

Genes

Genes tell the proteins and cells in your body how to look or act. If there is a change (variation or mutation) in these chromosomes or genes, your proteins and cells will not work properly and you can develop different diseases.

With CLL / SLL these changes can change the way your B-cell lymphocytes develop and grow, causing them to become cancerous.

The three main changes that can happen with CLL / SLL are called a deletion, a translocation and a mutation.

Common genetic changes in CLL / SLL

Deletion

A deletion is when part of your chromosome is missing. If your deletion is a part of the 13th or 17th chromosome it is called either “del(13q)” or “del(17p)”. The “q” and the “p” tell the doctor which part of the chromosome is missing. It is the same for other deletions.

Translocation

If you have a translocation, it means that a small part of two chromosomes – chromosome 11 and chromosome 14 for example, swap places with each other. When this happens, it’s called “t(11:14)”.

Other mutations

If you have a mutation, it may mean you have an extra chromosome. This is called Trisomy 12 (an extra 12th chromosome). Or you may have other mutations called IgHV mutation or Tp53 mutation. All these changes can help your doctor work out the best treatment for you., so please make sure you ask your doctor to explain your individual changes.

You need genetic testing before starting treatment.

Some of these tests you will only need to have once because the results stay the same throughout your lifetime. Other tests, you may need to have before every treatment, or at various times throughout your journey with CLL / SLL. This is because over the course of time, new genetic mutations can occur as a result of treatment, your disease or other factors.

The more common cytogenetic tests you will have include:

IgHV mutation status

You should have this before the first treatment only. IgHV does not change over time, so it only needs to be tested once. This will be reported as either a mutated IgHV or an unmutated IgHV.

FISH test

You should have this before first and every treatment. Genetic changes on your FISH test can change over time, so it is recommended that it is tested before starting treatment the first time, and regularly throughout your treatment. It can show if you have a deletion, a translocation or an additional chromosome. This will be reported as del(13q), del(17p), t(11:14) or Trisomy 12. While these are the most common variations for people with CLL /SLL you may have a different variation, however the reporting will be similar to these.

(FISH stands for Fluorescent In Situ Hybridisation and is a testing technique done in pathology)

TP53 mutation status

You should have this before first and every treatment. TP53 can change over time, so it is recommended that it is tested before starting treatment the first time, and regularly throughout your treatment. TP53 is a gene that provides the code for a protein called p53 to be made. p53 is a tumour suppressing protein and stops cancerous cells from growing. If you have a TP53 mutation, you may not be able to make the p53 protein, which means your body is unable to stop the cancerous cells from developing.

Why is it important?

It is important to understand these as we know not all people with CLL / SLL have the same genetic variations. The variations provide information to your doctor about the type of treatment that might work, or will likely not work for your particular CLL / SLL.

Please talk to your doctor about these tests and what your results mean for your treatment options.

For example, we know if you have a TP53 mutation, an unmutated IgHV or del(17p) you should not receive chemotherapy as it will not work for you. But this does not mean there is no treatment. There are some targeted treatments available that can work well for people with these variations. We will discuss these in the next section.

Treatment for CLL / SLL

Once all of your results from the biopsy, cytogenetic testing and the staging scans have been completed, your doctor will review these to decide the best possible treatment for you. At some cancer centres, your doctor may also meet with a team of specialists to discuss the best treatment option. This is called a multidisciplinary team (MDT) meeting.

How is my treatment plan chosen?

Your doctor will consider many factors about your CLL / SLL. Decisions on when or if you need to start and what treatment is best are based on:

- your individual stage of lymphoma, genetic changes and symptoms

- your age, past medical history and general health

- your current physical and mental wellbeing and patient preferences.

Other tests

Your doctor will order more tests before you start treatment to make sure your heart, lungs and kidneys are able to cope with the treatment. Extra tests may include an ECG (electrocardiogram), lung function test or 24-hour urine collection.

Your doctor or cancer nurse can explain your treatment plan and the possible side-effects to you. They can also answer any question you might have. It is important you ask your doctor and/or cancer nurse questions about anything you don’t understand.

Contact us

Waiting for your results can be a time of extra stress and anxiety for you and your loved ones. It is important to develop a strong network of support during this time. You will need them if you have treatment too.

Lymphoma Australia would like to be part of your support network. You can phone or email the Lymphoma Australia Nurse Helpline with your questions and we can help you to get the right information. You can also join our social media pages for extra support. Our Lymphoma Down Under page on Facebook is also a great place to connect with others around Australia and New Zealand who are living with lymphoma

Lymphoma care nurse hotline:

Phone: 1800 953 081

Email: nurse@lymphoma.org.au

Treatments options can include any of the following:

Watch and Wait (active monitoring)

Around 1 out of 10 people with CLL / SLL may never need treatment. It may stay stable with little to no symptoms for many months or years. But some of you may have several rounds of treatment followed by remission. If you don’t need treatment straight away or have time in between remissions, you will be managed with watch and wait (also called active monitoring). There are many good treatments for CLL available, and so it can be controlled for many years.

Supportive Care

Supportive care is available if you are facing serious illness. It can help you have fewer symptoms, and get better faster.

Leukemic cells (the cancerous B-cells in your blood an bone marrow) may grow uncontrollably and crowd your bone marrow, bloodstream, lymph nodes, liver or spleen. Because the bone marrow is crowded with CLL / SLL cells too young to work properly, your normal blood cells will be affected. Supportive treatment may include things like you having blood or platelet transfusions, or you may have antibiotics to prevent or treat infections.

Supportive care may involve a consultation with a specialised care team (such as cardiology if you have issues with your heart) or palliative care to manage your symptoms. It can also be having conversations about your preferences for you health care needs in the future. This is called Advanced Care Planning.

Palliative care

It is important to know that the Palliative Care team can be called on at any time during your treatment pathway not just at the end of life. Palliative care teams are great at supporting people with decisions they need to make towards the end of their life. But, they don’t just look after people who are dying. They are also experts in managing hard to control symptoms at any time throughout your journey with CLL / SLL. So don’t be afraid of asking for their input.

If you and your doctor decide to use supportive care, or stop curative treatment for your lymphoma, many things can be done to help you to stay as healthy and comfortable as possible for some time.

Chemotherapy (chemo)

You might have these medications as a tablet and/ or be given as a drip (infusion) into your vein (into your bloodstream) at a cancer clinic or hospital. Several different chemo medications may be used with an immunotherapy medicine. Chemo kills fast growing cells so can also affect some of your good cells that grow fast causing side effects.

Monoclonal Antibody (MAB)

You may have a MAB infusion at a cancer clinic or hospital. MABs attach to the lymphoma cell and attract other diseases fighting white blood cells and proteins to the cancer. This helps your own immune system to fight the CLL / SLL.

Some MABs may be given as an injection into your tummy instead of an infusion into your vein.

Common MABs used for CLL/SLL include rituximab and obinutuzumab.

Chemo-immunotherapy

Chemotherapy (for example, FC) combined with immunotherapy (for example, rituximab). The initial of the immunotherapy drug is usually added to the abbreviation for the chemotherapy regimen, such as FCR.

Targeted therapy

You may take these as a tablet at home or in hospital. Targeted therapies attach to the lymphoma cell and block signals it needs to grow and produce more cells. This stops the cancer from growing, and causes the lymphoma cells to die. For more information on these treatments, please see our oral therapies factsheet.

Stem-cell transplant (SCT)

If you are young and have aggressive (fast growing) CLL / SLL, a SCT may be used, but this is rare. To learn more about stem cell transplants please see out factsheets Transplants in Lymphoma

Starting Therapy

Many people with CLL/SLL will not require treatment when they are first diagnosed. Instead, you will go on watch and wait. This is common for people with stage 1 or 2 disease, and even some people with stage 3 disease.

If you have stage 3 or 4 CLL/SLL you may need to start treatment. When you start treatment for the first time, it is called first-line treatment. You may have more than one medicine, and these may include chemotherapy, a monoclonal antibody or targeted therapy.

When you have these treatments, you will have them in cycles. That means you will have the treatment, then a break, then another round (cycle) of treatment. For most people with CLL/SLL chemoimmunotherapy is effective to achieve a remission (no signs of cancer).

Genetic mutations and treatment

Some genetic abnormalities may mean that targeted therapies will work best for you, and other genetic abnormalities – or normal genetics may mean chemoimmunotherapy will work best.

Normal IgHV (unmutated IgHV) OR 17p deletion OR a mutation in your TP53 gene

Your CLL/SLL will probably not respond to chemotherapy, but it may respond to one of these targeted treatments instead:

- Ibrutinib, Acalabrutinib or Zanubrutinib (targeted therapy called a BTK inhibitor), may be given alone or with a monoclonal antibody called obinutuzumab

- Venetoclax & Obinutuzumab – venetoclax is a type of targeted therapy called a BCL-2 inhibitor, obinutuzumab is a monoclonal antibody

- Idelalisib & rituximab – idelalisib is a targeted therapy called a PI3K inhibitor, and rituximab is a monoclonal antibody

- You may also be eligible to participate in a clinical trial – Ask your doctor about this

Important information – Zanubrutinib is TGA approved, and was recently listed on the PBS for first-line treatment, meaning it will be much cheaper, or completely covered by Medicare if you need it.

However, Ibrutinib and Acalabrutinib are currently TGA approved, meaning they are available in Australia, but are not currently PBS listed as first-line treatment in CLL/SLL. This means they cost a lot of money to access. It may be possible to get access to the medications on “compassionate grounds”, meaning the cost is partly or fully covered by the pharmaceutical company. If you have normal (unmutated) IgHV, or 17p deletion, ask your doctor about compassionate access to these medications.

Lymphoma Australia is advocating for people with CLL/SLL by putting in a submission to the Pharmaceutical Benefits Advisory Committee (PBAC) to extend the PBS listing for these medications for first-line treatment; making these medications more accessible for more people with CLL/SLL.

You can also help raise awareness and put in your own submission to the PBAC for the PBS listing as first-line therapy by clicking here.

Mutated IgHV, or variation other than the ones above

You might be offered standard treatments for CLL/SLL including chemotherapy or chemoimmunotherapy. The immunotherapy (rituximab or obinutuzumab) will only work if your CLL/SLL cells have a cell surface marker called CD20 on them. Your doctor can let you know if your cells have CD20.

There are a few different medications and combinations your doctor can choose from if you have a mutated IgHV . These include:

- Bendamustine & rituximab (BR) – bendamustine is a chemotherapy and rituximab is a monoclonal antibody. They are both given as an infusion.

- Fludarabine, cyclophosphamide & rituximab (FC-R). Fludarabine and cyclophosphamide are chemotherapy and rituximab is a monoclonal antibody.

- Chlorambucil & Obinutuzumab – chlorambucil is a chemotherapy tablet and obinutuzumab is a monoclonal antibody. It is mainly given to older, more frail people.

- Chlorambucil – a chemotherapy tablet

- You may also be eligible to participate in a clinical trial

If you know the name of the treatment you will be having, you can find more information here.

Remission and Relapse

After treatment most of you will go into remission. Remission is a period of time where you have no signs of CLL/SLL left in your body, or when the CLL/SLL is under control and doesn’t need treatment.

Remission can last for many years, but eventually CLL usually comes back (relapses) and a different treatment is given.

Refractory CLL / SLL

Few of you may not achieve remission with your first-line treatment. If this happens, your CLL / SLL is called “refractory”. If you have refractory CLL / SLL your doctor will probably want to try a different medication.

Treatment you have if you have refractory CLL / SLL or after a relapse is called second-line therapy. The goal of second-line treatment is to put you into remission again.

If you have further remission, then relapse and have more treatment, these next treatments are called third-line treatment, fourth-line treatment and such.

You may need several types of treatment for your CLL/SLL. Experts are discovering new and more effective treatments that are increasing the length of remissions. If your CLL/SLL does not respond well to the treatment, or you relapse very quickly after treatment (within six months), your CLL/SLL is considered refractory. You will need a different type of treatment.

How second-line treatment is chosen

At the time of relapse, the choice of treatment will depend on several factors including.

- How long you were in remission for

- Your general health and age

- What CLL treatment/s you have received in the past

- Your preferences.

This pattern may repeat itself over many years. There are still many treatment options available if your CLL/SLL is refractory or relapses. Your options may include new targeted therapies, clinical trials or other common treatments for relapsed CLL/SLL such as:

- Venetoclax – a targeted therapy (BCL2 inhibitor) – a tablet

- Ibrutinib (Ibruvica), acalabrutinib (Calquence) or zanubrutinib (Brukinsa)- a targeted therapy (BTK inhibitor) – tablet

- Idelalisib and Rituximab – idelalisib is a targeted therapy (PI3K inhibitor) and rituximab is a monoclonal antibody. Idelalisib is a tablet and rituximab is given as drip into your veins.

More information on targeted therapies can be found here.

If you are young and fit (other than having CLL/SLL) you may be able to have an Allogeneic Stem cell transplantation.

We recommend that anytime you need to start new treatments, that you ask your doctor about clinical trials you may be eligible for. Clinical trials are important to find new medicines, or combinations of medicines to improve treatment of CLL / SLL in the future.

They can also offer you a chance to try a new medicine, combination of medicines, or other treatments that you would not be able to get outside of the trial.

Participating in a clinical trial is completely voluntary, and if you are interested in participating in a clinical trial, ask your doctor what clinical trials you are eligible for. If you choose not to join a clinical trial, you will still have access to the currently approved treatments for your situation.

You can also read our ‘Understanding Clinical Trials’ fact sheet or visit our webpage for more information on clinical trials

Prognosis for CLL / SLL – and what happens when treatment ends

Prognosis looks at what the expected outcome of your CLL / SLL will be, and what affect your treatment is likely to have.

CLL / SLL is not curable with current treatments. This means that once you are diagnosed, you will have CLL / SLL for the rest of your life….But, many people still live a long and healthy life with CLL / SLL. The purpose, or intent of treatment is to keep the CLL / SLL at a manageable level and ensure you have little, to no symptoms that affect your quality of life.

Everybody with CLL / SLL has different risk factors including age, medical history and genetics. So, it is very difficult to talk about prognosis in a general sense. It is recommended that you talk to your specialist doctor about your own risk factors, and how these may affect your prognosis.

Survivorship – Living with cancer

A healthy lifestyle, or some positive lifestyle changes after treatment can be a great help to your recovery. There are many things you can do to help you live well with CLL / SLL.

Many people find that after a cancer diagnosis, or treatment, that their goals and priorities in life change. Getting to know what your ‘new normal’ is can take time and be frustrating. Expectations of your family and friends may be different to yours. You may feel isolated, fatigued or any number of different emotions that can change each day. The main goals after treatment for your CLL / SLL is to get back to life and:

- be as active as possible in your work, family, and other life roles

- lessen the side effects and symptoms of the cancer and its treatment

- identify and manage any late side effects

- help keep you as independent as possible

- improve your quality of life and maintain good mental health

Cancer Rehabilitation

Different types of cancer rehabilitation may be recommended to you. This could mean any of a wide range of services such as:

- physical therapy, pain management

- nutritional and exercise planning

- emotional, career and financial counselling

We have some great tips in our factsheets available by clicking here.

Transformed Lymphoma (Richter’s transformation)

What is transformation

A transformed lymphoma is a lymphoma that was initially diagnosed as indolent (slow growing) but has transformed into an aggressive (fast growing) disease.

Transformation is rare, but may happen if genes in the indolent lymphoma cells become damaged over time. This can happen naturally, or as a result of some treatments, causing the cells to grow faster. When this happens in CLL / SLL it is called Richter’s Transformation (Also known as Richter’s Syndrome).

If this happens your CLL / SLL may transform into a type of Lymphoma called Diffuse Large B-cell Lymphoma (DLBCL) or even more rarely Hodgkin Lymphoma or a T-cell Lymphoma.

For more information on Richter’s Transformation please see the link below.